By Nasim Yousaf

Ever since the establishment of Pakistan and India in 1947, a web of falsehoods has been woven and disseminated through various means regarding the partition of India, the political ideologies of Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, and the misrepresented role of Allama Mashriqi in the freedom movement and resisting the division of the country. These inaccuracies, predominantly found in literature supporting the Two-States narrative, have only fueled animosity particularly between Muslims and Hindus, undermining peace and yielding profound adverse consequences. The moment has arrived to cease the suppression of truth and freedom of expression, and to revise the historical account, challenging the existing narrative on the partition of India.

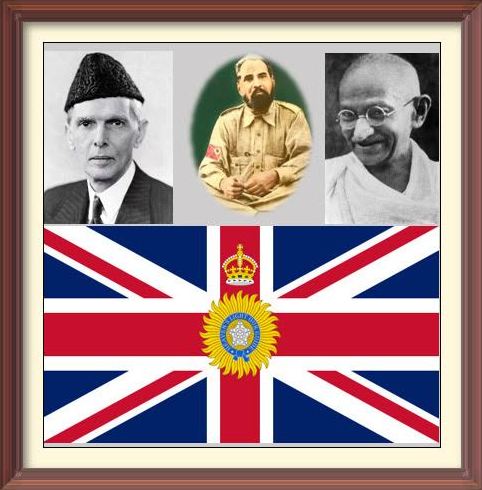

In reality, the British strategically utilized Jinnah and Gandhi to further their own agendas and maintain their control over the Indian subcontinent, ultimately leading to the division of India. My works, including a recently released 2.5-hour documentary titled “The Road to Freedom: Allama Mashriqi’s Historic Journey from Amritsar to Lahore,” and the published article “Are the history books telling the truth about Mashriqi, Jinnah, & Gandhi?” shed light on this historical manipulation and provide evidence that challenges established beliefs about the freedom movement and division.

In early 1939, preceding the issuance of his currency, Mashriqi declared his intent to end British rule by 1940 in “Al-Islah”. He subsequently set up a parallel government and delineated other significant measures. As World War II commenced in 1939 and the demand for independence grew stronger, the dynamics of power began to change. Allama Mashriqi rose as a formidable leader, confronting British rule and unsettling the established order, prompting apprehension among British rulers. This shift significantly affected both Jinnah and Gandhi, who were seen as potential allies by the British.

Despite Jinnah’s limited popularity and influence across India during that time, the British recognized him as the sole Muslim leader. Concurrently, Gandhi’s significance grew with his non-violent resistance, aimed at protecting British rule, aligning well with British interests, especially given Mashriqi’s objectives of overthrowing British rule. The strategic elevation of Jinnah and Gandhi by the British, along with their extensive media exposure, indicates the rulers’ intent to use them to serve their own objectives, following a historical pattern of aligning with individuals who supported their agenda.

Mashriqi’s plan necessitated the advancement of the “Divide and Rule” policy to sustain British dominance in the Indian subcontinent. Jinnah was tasked with advocating for a separate homeland, leading to the adoption of the Lahore Resolution (later Pakistan Resolution) in 1940. Simultaneously, Gandhi was entrusted with opposing the division of India, effectively fueling communalism and diverting public attention from the overarching demand for independence. Such delicate agreements were typically not formally documented.

To sustain the British Raj, the arrest of Mashriqi was crucial. In this endeavor, the support of Jinnah and Gandhi was sought, which proved advantageous, bolstering the importance of Jinnah and Gandhi with the rulers and safeguarding their own political careers. Allowing Mashriqi to rise to power would have meant an end to British rule and also an end to the political careers of Jinnah and Gandhi. Thus, a partnership among the three became indispensable.

This alliance resulted in the arrest of Mashriqi and a ban on the “Al-Islah” journal, leading to raids, the arrest of thousands of Khaksars, and various actions to eradicate the threat. The imprisonment of Mashriqi and the task of dividing Muslims and Hindus, given to Jinnah and Gandhi, not only allowed the British to maintain their rule but also fueled animosity between the two communities.

An essential event that underscores this collaboration was the deliberately orchestrated failure of the Jinnah-Gandhi meeting in 1944. The meeting was merely a political façade aimed at persuading the public that the British were genuinely interested in reaching a resolution. In truth, Jinnah and Gandhi, in line with the British desire to prevent an agreement, played into the hands of British rulers. The failure of the meeting exacerbated animosity between Muslims and Hindus, advancing the British ‘Divide and Rule’ policy.

After the failure, in an attempt to bridge the political differences, Mashriqi published “The Constitution of Free India, 1946 A.C.” However, Jinnah and Gandhi, pressured by the British, declined to accept Mashriqi’s document, despite it providing protection for the rights of all communities regardless of religion. Strikingly, both being attorneys, they never produced a constitution of their own to resolve Muslim-Hindu political conflicts, as the British did not want them to create such a constitution.

Furthermore, both Jinnah and Gandhi made significant shifts in their positions to assist the British in the division of India. Jinnah accepted the partition of Punjab and Bengal without resistance, aiming to become the founder and Governor General of Pakistan. In contrast, Gandhi transitioned from advocating for a united India to swiftly accepting division and persuading others to do the same, indicating their alignment with British objectives. This serves as substantial evidence confirming the existence of a partnership between Jinnah, Gandhi, and the British, carefully concealed.

The question of why Jinnah and Gandhi became pawns in the hands of the British can be traced back to their lack of grassroots support. Their survival in the political arena depended on the backing provided by the British rulers. Both Jinnah and Gandhi were well aware that if they did not assist the British, their political careers would crumble, and their prominent positions would come to an end. Their willingness to seek the transfer of power and accept the partition of India on British terms, without resistance and without a clear understanding of the boundaries of Pakistan and India, serves as a resoundingtestament to their dependence on British support.In contrast, Allama Mashriqi, who commanded the largest army and had substantial grassroots backing, chose not to collaborate with the British. This decision was resented by the rulers and clearly demonstrates that he did not rely on British assistance for his prominent position.

In the post-partition era, Jinnah and Gandhi received extensive recognition and promotion through various means, such as academic conferences, literature, research funding, and the erection of statues and memorials. Notably, even Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip paid their respects at Jinnah’s grave and Gandhi’s memorial, underscoring their association with the British establishment.

Gandhi’s legacy continues to gain prominence, evident in the accolades conferred upon him by British leaders like Prime Ministers Boris Johnson and David Cameron. Statues in his honor now adorn various countries, and the substantial amounts garnered through auctions of Gandhi’s memorabilia highlight the widespread recognition and reverence for him. Recent tributes from G20 leaders in September 2023 further emphasize this recognition, albeit overlooking the fact that his actions, along with those of Jinnah, led to the deaths of up to two million people, as well as widespread rapes and enduring consequences, even decades after the partition in 1947.

The souls of those who were victims of the political decisions of Jinnah, Gandhi, and a few others must surely be in agony and pain as they witness world leaders honoring Gandhi. This situation not only signifies hypocrisy in the global promotion of Gandhi’s non-violence, but it also neglects the violence inflicted upon Muslims, Hindus, Christians, and people of other faiths during the partition. Even in the present day, the world, including India, does not adhere to Gandhi’s principles of non-violence. If Gandhi’s methods were as effective as they are often touted to be, then the world should earnestly adopt them and cease the manufacturing of weapons and engagement in wars.

Moreover, the fervent promotion of Gandhi by pivotal powers aims to encourage other nations to embrace his passive and submissive methods. However, this advocacy for non-violence on the international stage, championed through Gandhi’s ideals, stands in stark contrast to the aggressive actions these influential nations readily engage in, revealing profound two-facedness in their global stance.

Digging deeper into this perspective, it becomes increasingly astonishing how the devastating toll of killings and rapes during India’s partition, often attributed in part to the roles of Jinnah and Gandhi, seems conspicuously absent from the focus of world powers, human rights groups, and activists. Remarkably, there are no annual commemorations dedicated to the victims of this tragic chapter in India’s history, encompassing Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, and other non-Muslims.

Moreover, the extraordinary reverence bestowed upon both Jinnah (according to a news report, Jinnah’s statue is to be erected in London) and Gandhi, particularly by the British, sheds light on their elevated status as British allies. This scenario stands as an unparalleled anomaly in human history, where the former rulers of British India extend such honor to individuals who ostensibly played significant roles in the dissolution of their own rule. The question is: why do the UK and pivotal powers actively promote Jinnah and Gandhi? In addition to the reasons given earlier in this piece, the answer is simple – to perpetuate the political conflicts between Jinnah and Gandhi, thereby justifying the partition. Furthermore, this supports hindering any chance of reunification among Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, which is not in the interest of any world power.

Conversely, the British establishment and other influential powers actively suppressed the legacy of Allama Mashriqi, a brilliant thinker and one of the greatest minds the world has ever witnessed. His aim was to unite humanity, encouraging research to establish a connection or even potentially ‘shake hands’ with the Creator. His goal was to redirect human energy towards research, development, and progress, rather than channeling energies and resources into the production of lethal weapons. Mashriqi’s ideologies surpassed those of Gandhi. Mashriqi’s role in the freedom movement and ending British rule is much greater than that of Jinnah and Gandhi, a topic that warrants a dedicated work. Yet, he remains suppressed because his ideas challenge the interests of powerful nations driven by self-interest, and they refuse to acknowledge that Mashriqi played a significant role in ending British rule due to their ego and vested interests.

Nevertheless, the deep-seated British resentment and deliberate suppression or distortion of Mashriqi’s pivotal role in the independence movement emphatically affirms his leading role in winding-up British rule. For instance, the research libraries of British academic institutions are replete with material related to Jinnah and Gandhi. However, the extensive records and contributions of Mashriqi, spanning from 1930 until his passing in 1963, are conspicuously absent from these repositories. Even his historic publication, “Al-Islah” journal, remains noticeably absent from their research libraries.

Furthermore, while the British had the resources and inclination to film Jinnah and Gandhi on numerous occasions, including their funerals, they notably neglected to document even Mashriqi’s funeral, despite it being one of the largest gatherings in both the East and the West.

Another telling disparity can be observed at the University of Cambridge, which has not established any scholarships, released photographs, created chairs, or erected a plaque on its premises to honor Mashriqi—a figure who made significant contributions to academic history at the university.

History shows that Jinnah and Gandhi’s methods couldn’t bring freedom. In fact, their strategies are absent in contemporary quests for independence; only the naive could embrace such a narrative. Crediting them is merely upholding a prevailing myth. Given this, investing time in writing, reading, or discussing their politics is utterly futile. Moreover, delving into Jinnah and Gandhi’s conflicting politics perpetuates the divisive “Divide and Rule” strategy, worsening tensions between Muslims and Hindus and negatively impacting Pakistan-India relations. Abandoning this approach is crucial for achieving lasting peace.

The reason British establishment gives credit to the methods of Jinnah and Gandhi in ending their rule to soothe their own pride. Simultaneously, they downplay and deny Mashriqi’s formidable threat in the culmination of their rule, as it challenges their sense of pride.

The harsh truth remains unchanged: Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan uphold strikingly similar state narratives to avoid British resentment, reflecting that the establishments of these three countries have yet to break free from British influence Jinnah is celebrated as Pakistan’s founder, while Gandhi is revered as India’s liberator.

In contrast, the documentary delves deeper into these hidden truths, revealing the dark side of Jinnah, Gandhi, and the British rulers during a tumultuous period – details that historians have deliberately avoided. It discards the idea that Jinnah created Pakistan and Gandhi is the champion of India’s freedom.

In addition to challenging established narratives, Allama’s documentary unveils the British Transfer of Power in 1947, denying its voluntary character. It conveys that the transfer was not genuinely an act of British goodwill but rather influenced by the looming power of Mashriqi. The documentary meticulously presents a wealth of archival and historical documents, complemented by newspaper reports from that era, all of which contribute to a body of evidence that is both compelling and resistant to refutation. What truly distinguishes this film is its unparalleled access to information directly from the Mashriqi family and the Khaksars, integral figures within the freedom movement. This exclusive perspective, previously inaccessible to historians, bestows upon us a fresh and invaluable comprehension of the historical events in question. For those seeking deeper insights, delving into my published works becomes an imperative step.

Another lesser-known aspect this film sheds light on is the involvement of uniformed women Khaksars, empowered by Mashriqi during the 1930s, a period when women in the West were still fighting for rights equal to men.

The documentary is a must-watch before it potentially faces bans, as it challenges the established perspective by asserting that historical accounts in textbooks are far from the truth. It staunchly refuses to echo the accounts of historians, which are typically aligned with their respective State interpretations, resulting in bias and imbalance. Presenting the unvarnished truth would lead to their termination.

The documentary, “The Road to Freedom: Allama Mashriqi’s Historic Journey from Amritsar to Lahore,” offers Mashriqi’s concealed and unexplored perspective on various matters. It encourages the exploration of new and impartial viewpoints, which is essential for individuals to learn from past mistakes and gain a deeper understanding of history

In conclusion, it’s imperative to question historical stories and reevaluate the roles and motivations of prominent figures in shaping history. Only through a comprehensive understanding of the past, one that includes overlooked perspectives and suppressed truths, can we hope to move forward in a more informed and just manner. The suppression of certain narratives for political expediency should not be allowed to distort the true lessons of history and the complex dynamics that shaped pivotal events like the partition of India. Let us embrace the pursuit of truth and a more complete understanding of history, even if it challenges established beliefs and accounts.

Copyright © 2023 Nasim Yousaf

Author Nasim Yousaf, both a dedicated researcher and the grandson of Allama Mashriqi, brings a unique perspective to his research. His familial connection enhances his ability to uncover lesser-known historical insights. He has authored 18 meticulously researched books and digitized 19 rare publications, including Allama Mashriqi’s 1934 journal, Al-Islah.

Yousaf’s scholarly contributions have earned global recognition, with his works being housed in prestigious institutions such as Columbia, Harvard, Cornell, and Stanford universities, as well as the Library of Congress and state libraries worldwide.

For more information about the author and his work, interested individuals can visit these YouTube links:

Author’s bio:

Link to the documentary he produced:

Hisbooks in global libraries:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hm5C6BfasNw