ISLAMABAD, MAY 1 (DNA): The genocide of the Rohingya in Myanmar is a systematic campaign rooted in Buddhist chauvinism, mono-ethnic nationalism, and the denial of Rohingya identity. Addressing atrocities of this scale requires moral courage, strong legal mechanisms, and a unified global response. As such, it represents a critical test of the international community’s moral and legal resolve. Justice can only be achieved through sustained international pressure, comprehensive documentation, and inclusive political reforms.

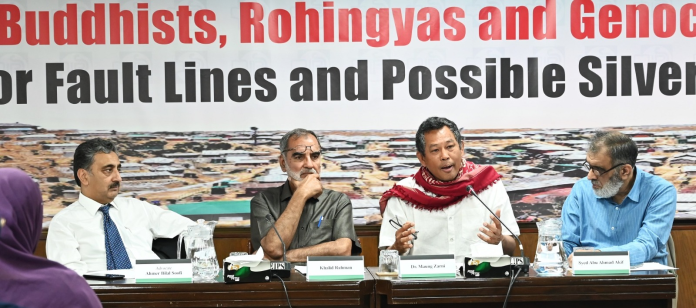

This was observed at a seminar titled “Buddhists, Rohingyas, and Genocide: Major Fault Lines and Possible Silver Linings,” hosted by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), Islamabad. The speakers included Myanmar-born scholar and rights activist Dr Zarni as the keynote speaker, Ahmer Bilal Soofi, senior advocate and founding president of the Research Society of International Law, Syed Abu Ahmad Akif, former federal secretary, and Khalid Rahman, chairman IPS.

Dr Zarni described the primary fault line behind the genocide as the deeply embedded Buddhist chauvinism in Myanmar, where Buddhists dominate state institutions and deny respect and fundamental rights to religious minorities. The Rohingya identity is denied domestically but protected under international law, he stated, adding that the 1982 Citizenship Law effectively rendered the Rohingya stateless.

He recounted the 2017 military campaign, in which more than 300 Rohingya villages were razed in just three months through organized arson, indiscriminate killings, and mass rapes, acts supported by the predominantly Buddhist population. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya sought refuge in other countries, especially Bangladesh.

He also criticized the silence of Myanmar’s intellectuals, media, and educated classes, noting that many knowingly supported the military’s actions. “Genocide is not spontaneous. It is planned, and what matters is how societies act on what they know,” he said.

Dr Zarni likened the ideological underpinnings of the Rohingya genocide to Hindutva in India and Zionism in Israel, where violence is framed as self-defense against imagined threats to national or religious identity.

Ahmer Soofi emphasized that religion should remain a matter of individual choice and that the right to practice any faith must be safeguarded under domestic and international law. Drawing on Islamic principles and Pakistan’s Constitution, he stressed that Islam mandates the protection of all human lives, regardless of religious affiliation. He noted that this principle aligns closely with Article 2 of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

Citing that documentation by a UN investigation commission led to convictions after the Bosnian genocide, Soofi underscored the need for a dispassionate and objective documentation strategy to build a legal case for the Rohingya at various levels.

Khalid Rahman highlighted that the selective application of international law undermines its credibility and perpetuates cycles of violence. He said that human rights violations are no longer confined to specific regions, and selective advocacy only fuels further oppression. He cited the situations in Palestine and Indian-occupied Kashmir as parallels to the plight of the Rohingya.

The discussion also highlighted some emerging signs of hope. Dr Zarni pointed out that Myanmar’s military, though still the primary perpetrator of atrocities, has weakened and recently expressed willingness to repatriate some 180,000 Rohingya refugees from Bangladesh. Moreover, despite a general rollback of US foreign aid under the Trump administration, Rohingya aid was exempted, indicating some measure of international concern.