BELÉM, NOV 10 (AFP/APP): An odor of oil hung over last year’s UN climate conference in Baku, capital of fossil fuel-rich Azerbaijan.

Starting Monday, the 50,000 participants of COP30 will instead feel the heavy, humid air of the Amazon rainforest in Belem, Brazil, where they face the daunting task of keeping global climate cooperation from collapsing.

Unfazed, President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva insisted on holding the event here despite a dire shortage of hotel rooms.

His aim: to make the Amazon itself open the eyes of negotiators, observers, businesses and journalists – in a city where locals carry umbrellas both to shield themselves from the blazing morning sun and from the tropical downpours that follow in the afternoon.

“It would be easier to hold the COP in a rich country,” Lula declared in August. “We want people to see the real situation of the forests, of our rivers, of our people who live there.”

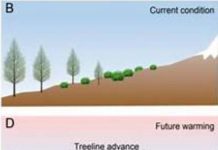

The Amazon rainforest, which plays a vital role in the fight against global warming through its absorption of greenhouse gases, is itself plagued by a host of ills: deforestation, illegal mining, pollution, drug trafficking, and all manner of rights abuses against locals, especially Indigenous peoples.

While the Brazilians have been active on the diplomatic front for the past year, they’re lagging behind on logistics. Many pavilions were still under construction as of Sunday.

“There is great concern about whether everything will be ready on time from a logistical standpoint,” a source close to the UN told AFP. “Connections, microphones, we’re even worried about having enough food,” the source added.

The real uncertainty lies in what will actually be negotiated over the next two weeks: Can the world come together to respond to the latest, catastrophic projections for global warming?

How can a clash between rich nations and the developing world be avoided?

And where will the money come from to help countries hit by cyclones and droughts — like Jamaica, devastated in October by one of the world’s most powerful hurricane in nearly a century, or the Philippines, battered by two deadly typhoons in just two weeks?

And what to make of the “roadmap” on fossil fuels that Lula put on the table Thursday at the leaders’ summit? The oil industry — and the petrostates that depend on it — have rallied since the world agreed in Dubai in 2023 to begin the gradual transition away from fossil fuels.

“How are we going to do it?” Andre Aranha Correa do Lago, the Brazilian president of COP30 said Sunday. “Is there going to be a consensus about how we are going to do it? This is one of the great mysteries in COP30.”