The Taliban have positioned themselves as solely concerned with creating an Islamic emirate in Afghanistan and having no inclination to operate beyond the borders of the Central Asian state, but have been consistent in their refusal to expel Al Qaeda, even if the group is a shadow of what it was when it launched the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington 20 years ago

Dr. James M. Dorsey

Taliban advances in Afghanistan shift the Central Asian playing field on which China, India and the United States compete with rival infrastructure-driven approaches. At first glance, a Taliban takeover of Kabul would give China a 2:0 advantage against the US and India, but that could prove to be a shaky head start.

The potential fall of the US-backed Afghan government of President Ashraf Ghani will shelve if not kill Indian support for the Iranian port of Chabahar that was intended to facilitate Indian trade with Afghanistan and Central Asia.

Chabahar was also viewed by India as a counterweight to the Chinese-supported Pakistani port of Gwadar, a crown jewel of the People’s Republic’s transportation, telecommunications and energy-driven Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The United States facilitated Indian investment in Chabahar by exempting the port from harsh US sanctions against Iran. The exemption was intended to “support the reconstruction and development of Afghanistan.”

However, with negotiations with Iran about a revival of the 2015 international nuclear agreement stalled, the United States announced in July together with Afghanistan, Pakistan and Uzbekistan plans to create a platform that would foster regional trade, business ties and connectivity.

The connectivity end of the plan resembled an effort to cut off one’s nose to spite one’s face. It would have circumvented Iran and weakened Chabahar but potentially strengthened China’s Gwadar alongside the port of Karachi.

That has become a moot point with the plans certain to be shelved as the Taliban move to take over Kabul and form a government that would be denied recognition by at least the democratic parts of the international community.

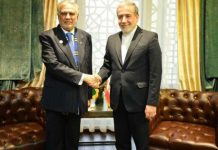

Like other Afghan neighbors, neither Pakistan nor Uzbekistan or for that matter China are likely to join a boycott of the Taliban. On the contrary, China last month made a point of giving a visiting Taliban delegation a warm welcome.

Recognition by Iran, Central Asian states and China of a Taliban government is however unlikely to be enough to salvage the Chabahar project. “Changed circumstances and alternative connectivity routes are being conjured up by other countries to make Chabahar irrelevant,”.

The Taliban have sought to reassure China, Iran, Uzbekistan and other Afghan neighbors that they will not allow Afghanistan to become an operational base for jihadist groups, including Al Qaeda and Uighur militants of the Turkestan Islamic Party (TIP).

The Taliban have positioned themselves as solely concerned with creating an Islamic emirate in Afghanistan and having no inclination to operate beyond the borders of the Central Asian state, but have been consistent in their refusal to expel Al Qaeda, even if the group is a shadow of what it was when it launched the 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington 20 years ago.

The TIP has occasionally issued videos documenting its presence in Afghanistan but has, by and large, kept a low profile in the country and refrained from attacking Chinese targets in Afghanistan or across the border in Xinjiang.

As a result, the Taliban reassurance was insufficient to stop China from repeatedly advising its citizens to leave Afghanistan as soon as possible.

“Currently, the security situation in Afghanistan has further deteriorated … If Chinese citizens insist on staying in Afghanistan, they will face extremely high-security risks, and all the consequences will be borne by themselves,” the Chinese foreign ministry said.

The fallout of the Taliban’s sweep across Afghanistan, despite the group’s assurances, is likely to affect China beyond Afghan borders, perhaps no more so than in Pakistan, a major focus of the People’s Republic’s single largest Belt-and Road-related investment.

The investment has made China a target for attacks by militants primarily Baloch nationalists. However, the killing in July of nine Chinese nationals in an explosion on a bus transporting Chinese workers to the construction site of a dam in the northern mountains of Pakistan, a region more prone to attacks by religious militants, raises the specter of jihadists also targeting China. It was the highest loss of life of Chinese citizens in recent years in Pakistan.

The attack occurred amid fears that the Taliban will bolster ultra-conservative religious sentiment in Pakistan that celebrates the group as heroes whose success enhances the chances for austere religious rule in the world’s second-most populous Muslim-majority state.

“Our jihadis will be emboldened. They will say that ‘if America can be beaten, what is the Pakistan army to stand in our way?’” said a senior Pakistani official.

Indicating Chinese concern, China has delayed the signing of a framework agreement on industrial cooperation that would have accelerated the implementation of projects that are part of the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

Said scholar Kamran Bokhari: “Regime change is a terribly messy process. Weak regimes can be toppled; replacing them is the hard part. It is only a matter of time before the Afghan state collapses, unleashing chaos that will spill beyond its borders. All of Afghanistan’s neighbors will be affected to varying degrees, but Pakistan and China have the most to lose.”

The demise of Chabahar and/or the targeting by the Taliban of Hazara Shiites in Afghanistan could potentially turn Iran into a significant loser too.

Dr. James M. Dorsey is an award-winning journalist and scholar and a senior fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Middle East Institute