Military veterans from India and Pakistan foresee a slim chance of a full-fledged war between the two nuclear neighbors, dubbing it an “inconceivable” idea on the 56th anniversary of the 1965 war.

They also called for “political engagement” to resolve long-pending disputes, including the Kashmir issue.

Retired Lieut. Gen. HS Panag, an Indian war veteran, who participated in the 1971 war as a young captain against Pakistan, observed that the “nuclear factor” massively diminished the chances of a full-scale war.

“In 1998, both countries became nuclear powers. Now nuclear nations don’t fight a full-scale war, because nuclear capabilities come into play at some point in time and Pakistan has been practicing nuclear brinkmanship to its advantage,” Panag told Anadolu Agency while accusing Islamabad of waging a “proxy war” in the disputed Jammu and Kashmir region.

“Wars and conflicts continue between nations and they never end … but in the modern era with nuclear weapons, the concept of an all-out war is over. It no longer can take place,” he said. “What can happen is, below the threshold of war and there are also limits to that.”

Stating that India has also refrained from attacking Pakistan because of the same reason, he said Pakistan “cannot be decisively defeated by India.”

Echoing Panag’s views, retired Lieut. Gen. Talat Masood, who participated in two wars against India, in 1965 and 1971, also rejected the possibility of a full-fledged war even if the nuclear factor is kept aside.

“Yes, nuclear capability is a factor but if even they are not nuclear, it would make no sense to go into full-fledged war in this era,” Masood, who served in an armored division that took part in a fierce tank battle on the eastern borders in the 1965 war, told Anadolu Agency.

The battle, involving hundreds of tanks from both sides, took place at Chawinda village that sits on the Pakistan-India border near northeastern Sialkot district, is considered the second greatest tank battle after World War II.

“(In case of an all-out war) You will push your country back 15 – 20 years, apart from alienating yourself from the international community. Things will get harder for your people, the economy will be shattered and matters will be complicated further,” he said.

It is not a “sensible” and “conceivable” idea that the two countries will make a “blunder” to go into a war, he added.

Retired Major Ikram Sehgal, who was an aviation pilot in post-1965 war skirmishes along the border between then East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, and India and six years later in the 1971 war, also ruled out the chances of an all-out war.

“An all-out war means, it may turn into a nuclear conflict. And in that case, the winner and the loser will stand nowhere,” Sehgal said to Anadolu Agency.

Brig. M. P. S. Bajwa, an army veteran who commanded an Indian brigade during the 1999 Kargil skirmish against Pakistan, said, “It is very unlikely because both countries are nuclear-armed and they apparently have realized it is not an option.”

Pakistan and India are among a few select countries with nuclear arsenals. India joined the nuclear club long before Pakistan, in 1974, prompting Islamabad to follow suit. Pakistan silently developed its nuclear capabilities in the 1980s, when it was an ally of the US in the first Afghan war against the crumbling Soviet Union.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, India currently possesses between 80 and 100 nuclear warheads, while Pakistan holds 90 to 110.

POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT

The 17-day war that began Sept. 6, 1965, was an escalation of irregular fighting that started regarding Kashmir, a sore point between the two countries ever since partition in 1947.

The war eventually ended with a draw, following a peace agreement, brokered by the then-prime minister of the now-defunct Soviet Union in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan.

Nonetheless, both countries declared victory.

Pakistan, since then, has been celebrating Sept. 6 as Defense Day.

Insisting that another war will further complicate matters, Masood sees a “political engagement” as the only option to resolve long-smoldering disputes between the two nuclear-armed neighbors.

“The only answer lies in (a) political solution. The two sides have to engage politically. There is no other way,” he said.

The political engagement, he thought, will eventually facilitate cultural and economic engagements.

Supporting Masood’s view, Bajwa said Islamabad and New Delhi should “sit and talk” to resolve their pending issues.

Sehgal, who authored the bestseller, Escape from Oblivion — his autobiography as a prisoner of war — nonetheless reckoned that India would never hold any meaningful talks on Kashmir as “giving up Kashmir means giving up several other states,” a reference to several northeastern Indian states hit by separatist movements.

Panag opined that India and Pakistan are engaged in a “primordial struggle” starting from the partition of India, making an all-out war between the nuclear-armed countries “unlikely.”

Kashmir is held by India and Pakistan in parts and claimed both in full. A small sliver of Kashmir is also held by China.

Since they were partitioned in 1947, the two countries have fought three wars — in 1948, 1965 and 1971 — two of them over Kashmir.

Some Kashmiri groups in Jammu and Kashmir have been fighting against Indian rule for independence, or unification with neighboring Pakistan.

According to several human rights organizations, thousands have reportedly been killed in the conflict in the region since 1989.

Relations between India and Pakistan plummeted to a new low after August 2019, when India scrapped the longstanding special status of the disputed Jammu and Kashmir region.

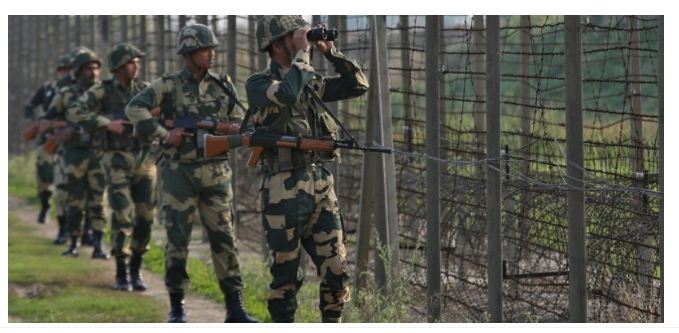

Since then, the two border forces have been engaged in almost daily clashes at the Line of Control (LoC), a de facto border that splits the scenic Kashmir valley between the two rivals until the two sides agreed to honor a 2003 cease-fire agreement in February.

Apart from Kashmir, the two countries have been locked in a string of sea-and-land disputes, amid several “successful” missile tests.

WAR GAVE NEW POLITICAL DYNASTIES TO INDIA, PAKISTAN

Hours after signing the peace agreement in 1966, Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri mysteriously died in Tashkent, leading to persistent conspiracy theories. The city hosts his bust and a road named after Shastri.

The difference also arose between Pakistan President Ayub Khan and his Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in Tashkent, soon after signing the agreement. Bhutto parted ways and launched his own party — the Pakistan People’s Party and rose to become prime minister.

In India, Shastri’s death paved the way for 48-year old Indira Gandhi to become the first female prime minister in India. With a brief interlude of two years, she ruled the country until October 1984 when she was assassinated by her bodyguards.

Tashkent, not only gave South Asia the Mughal dynasty but two political families — Gandhi and Bhutto.