BY MUHAMMAD MOHSIN IQBAL

There was a time when a visit to the cinema once a month was regarded as wholesome family entertainment. In the 1970s, Urdu and Punjabi cinema possessed a charm, vigour and moral clarity that modern audiences can scarcely imagine. The heroes were unmistakably heroic, the villains unapologetically villainous, and the dialogue—often thunderous—left a lasting imprint on the collective memory. Among the most commanding of those voices was Mazhar Shah, whose resonant tone and fierce screen presence dominated Punjabi and Urdu films for decades. From 1958 to 2016, he appeared in nearly 193 films, mostly portraying villains whose rage, arrogance and booming Punjabi tirades became legendary.

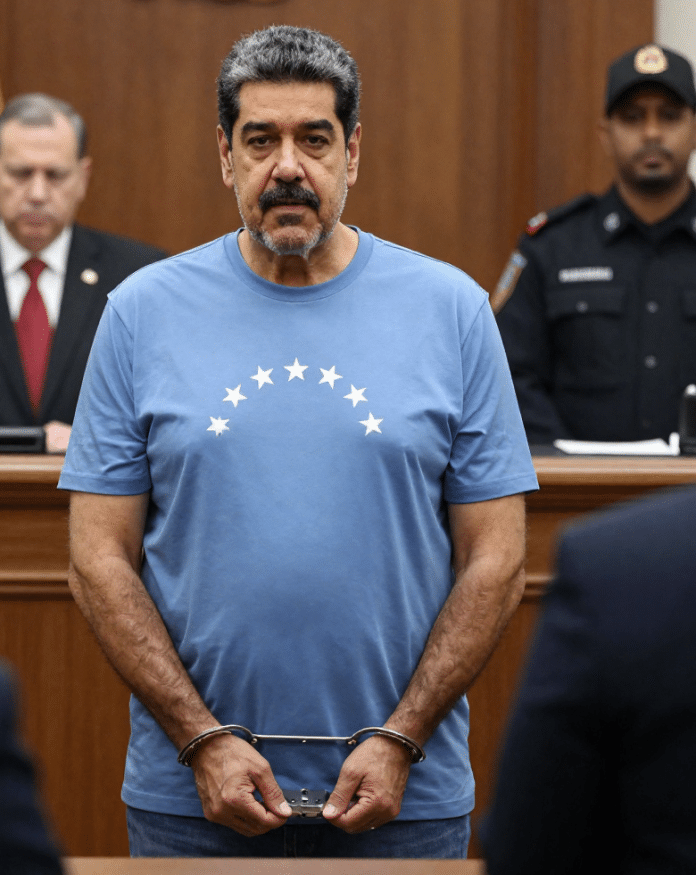

One particular scene remains etched in popular memory. Mazhar Shah as a villain in a film sends a proposal to the heroine’s father, demanding her hand in marriage. When the father refuses, the rejection ignites fury. With a single command—delivered in that unmistakable, high-pitched growl—Mazhar Shah orders his henchmen to seize the girl. She is abducted from her home and brought to the villain’s Dai’ra (Camp), the scene unfolding with the exaggerated drama typical of its era. I had not thought of that film for years, yet it resurfaced vividly in my mind when news broke of the arrest of the Venezuelan President and his wife on the alleged orders of the President of the United States. The cinematic echo was unsettling. In this real-life drama, neither the American President is a traditional villain nor the Venezuelan President a helpless heroine, yet the visual and symbolic resemblance was impossible to ignore.

Venezuela, long at odds with Washington, has consistently used international platforms, particularly the United Nation’s General Assembly sessions to criticise American policies and Presidents. Its leaders have spoken defiantly, often invoking sovereignty, resistance and dignity. Against this backdrop, the manner in which the Venezuelan President was apprehended appeared less like a routine legal action and more like a scene lifted from a political thriller. The operation, code-named “Operation Absolute Resolve,” reportedly involved airstrikes on Venezuelan military targets, resulting in dozens of deaths, before the President and his wife were captured in Caracas and flown to New York to face federal charges ranging from narco-terrorism conspiracy to weapons offences. The charges stem from a 2020 indictment accusing him of leading the so-called “Cartel of the Suns” and collaborating with armed groups such as FARC.

What makes this episode particularly disturbing is not merely its dramatic execution but the strategic and legal context surrounding it. Venezuela is not a defenceless state. Its military, ranked 50th out of 145 countries by the Global Firepower Index for 2025, possesses significant manpower and a defence budget of around $4.1 billion. Its geography and force structure make it regionally formidable, especially in defensive roles. More striking still is its natural wealth. Venezuela holds an estimated $14.3 trillion in natural resources, driven primarily by its vast oil reserves—approximately 303 billion barrels, the largest proven reserves in the world, accounting for nearly 18 per cent of the global total. This positions Venezuela as a pivotal energy actor, surpassing even Saudi Arabia and Iran in sheer reserves, though sanctions and infrastructural decay have blunted this advantage.

Yet military strength and resource wealth proved irrelevant in the face of overwhelming power exercised beyond the usual boundaries of international conduct. No explicit law in the United States—or in any other country—authorises the use of military force to arrest or kidnap a foreign head of state for domestic prosecution. Such actions collide directly with established principles of international law, including the prohibition on the use of force enshrined in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, the doctrine of non-intervention, and the customary rule of head-of-state immunity. No UN Security Council mandate was obtained, and attempts to frame drug trafficking as a form of armed attack fail to meet accepted legal standards.

The United States justifies its action through a contested blend of domestic precedents; federal criminal indictments with extraterritorial reach, presidential authority under Article II of its Constitution, and legal doctrines such as Ker–Frisbie, which allow courts to try defendants regardless of how they are brought before them. Historical parallels, notably the 1989 capture of Panama’s Manuel Noriega through “Operation Nifty Package” are cited as precedent. Moreover, Washington argues that since it has not recognised the Venezuelan leader as legitimate since 2019, he cannot claim sovereign immunity. International legal scholars, however, overwhelmingly reject this reasoning, warning that substituting domestic interpretations for international norms erodes the very foundation of the global order.

If such incidents become normalised, the future of world peace appears bleak. When powerful states assume the right to seize foreign leaders by force, weaker nations will feel perpetually insecure, diplomacy will be hollowed out, and the incentive to resolve disputes through dialogue or legal mechanisms will diminish. The established system of extradition, governed by treaties and judicial review, exists precisely to prevent such unilateralism.

The way forward lies in restraint and recommitment to international law. Global peace cannot survive if cinematic impulses replace legal principles. Powerful states must resist the temptation to act as judge, jury and executioner beyond their borders. Multilateral institutions, however imperfect, must be strengthened, not bypassed. Otherwise, the world risks descending into a disorder where every thunderous command of “bring him” or “bring her” echoes not from a cinema screen, but across a fractured and fearful international stage.