Ishtiaq Ahmed

Since 1979, Afghanistan has been a theater of two major global conflicts. We know what happened in the first instance: The Afghan people not only bore the brunt of the war but also had to face its deadly consequences. Global apathy fueled ethno-religious fissures. The brewing conflict finally resurged to threaten international peace and the world was left with no choice but to intervene in the war-torn nation.

The second instance — the longest war in Afghan history — ended last year, producing an unprecedented humanitarian disaster. The world is again unwilling to rescue the Afghans from its ravages. With a simmering crisis and sources of conflict intact, Afghanistan will descend a familiar path, slowly but surely.

The scale of its current disaster is enormous. The evidence furnished by UN agencies is stark: Over 24 million people — more than half of the Afghan population — need emergency assistance to survive. More than a million children under the age of five face a high risk of dying from starvation. The economy has contracted by almost half in the past year and the official poverty rate could soon reach 97 percent. Last year alone, 1.3 million Afghans were internally displaced. Millions more have taken refuge abroad.

Of course, much of this disaster is human-made, rooted in persistent ethnic conflict, religious terrorism and foreign aggression. But nature is also not so kind to the Afghans. A protracted drought has devastated agriculture and livestock, compounding the food crisis. Last month, a devastating earthquake also struck the southeastern provinces, causing massive loss of life and property and exposing half a million people to hunger and disease, according to UN estimates.

The global apathy to Afghan suffering is writ large. In March, the UN appealed for $4.4 billion in emergency support from donor nations. It got merely half of this amount and that too with severe restrictions on its disbursement by UN relief agencies due to Western sanctions against the de facto Taliban regime. Some of these restrictions have relaxed over time, but serious issues continue to hamper the delivery of essential food and health supplies to the bulk of the rural Afghan population.

Other sources of support include the Humanitarian Trust Fund for Afghanistan, set up by the Organization of Islamic Cooperation in March. Saudi Arabia has provided the bulk of this support with a grant of $30 million. But contributions to this fund and other bilateral commitments pale in comparison to the gravity of the crisis. Neighboring countries are already overstretched due to the Afghan refugee presence. Pakistan, for instance, has hosted millions of Afghan refugees for the last four decades. Several hundred more have arrived since last year. It has limited economic capacity to help, but still does.

The primary responsibility for mitigating Afghans’ humanitarian suffering falls on the shoulders of the US.

Ishtiaq Ahmad

No matter what other countries do to help the Afghans — out of Muslim solidarity or geographical affinity — the primary responsibility for mitigating their humanitarian suffering falls on the shoulders of the US. This is where the real problem lies. About $9.5 billion of funds from the Afghan central bank were frozen by the US and its European allies as they exited the 20-year war last August. Out of this, $7 billion was held in US banks and the remaining $2.5 billion in European banks.

The Biden administration has unfrozen $3.5 billion in Afghan assets, but it is yet to decide how to safely transfer them to the UN and other humanitarian organizations in Afghanistan without involving the Taliban. US officials are concerned that money meant for humanitarian operations may end up in Taliban hands if donors use the Afghan central bank.

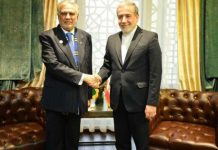

US Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas West, accompanied by officials from the Treasury Department, last week met with a Taliban delegation led by acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi in Doha, but they failed to solve the financial row. However, in a promising sign, both sides agreed to keep the conversation going.

This was the first high-level contact between US and Taliban officials since March, when the Taliban government decided to ban secondary schooling for girls. Since then, more restrictions have followed. Last week’s loya jirga (grand assembly) of more than 3,000 Afghan tribal elders and religious scholars in Kabul clearly suggests that the Taliban regime is in no mood for compromising on women’s and minority rights. Without such a compromise, it should forget about being recognized by the world.

The Taliban leadership may, however, agree to negotiate on this issue in exchange for the US unfreezing Afghan funds. The economic crisis is a potential driver of conflict and misery in Afghanistan. But once the country’s humanitarian woes subside, the Taliban regime can claim international legitimacy on the basis of domestic stability.

Therefore, the Biden administration must find a way to deliver the money, which belongs to Afghanistan and can provide direly needed relief to its hapless population. The best option would be to use the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the principal world institution supervising humanitarian activities in Afghanistan. UN relief agencies such as the UN Food Program and the World Health Organization have extensive experience in dealing with the financial complexities involved in humanitarian operations.

In fact, the US and its European allies owe a lot more to the Afghan people. Is it not ironic that the US spent $2 trillion in waging the war and is now squabbling over a mere $7 billion in relief? The humanitarian disaster Afghanistan faces today is a direct outcome of this war. Yet, American commitment to mitigating this disaster is only $772 million. The Afghans, resilient as they are for having gone through so much pain and suffering, do not deserve such a rebuke.

To cut a long story short, back in the 1980s, the US blundered by walking away from Afghanistan. The consequences were grave. Failure to learn from history this time around could push the US, and the rest of the world, into even greater danger. This is an outcome we must avoid at all costs.

• Ishtiaq Ahmad is a former journalist who has been vice chancellor of Sargodha University in Pakistan and Quaid-e-Azam Fellow at the University of Oxford.