by Mudassar Javed Baryar

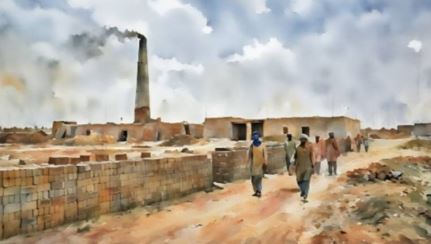

Aisha Hassan’s When the Fireflies Dance feels less like a debut novel and more like an early tremor of a writer who understands that Pakistan’s next great fiction will not emerge from cities, campuses, or intellectual salons, but from the smog-choked peripheries where labourers breathe in their own slow undoing. In this enthralling first work, Hassan writes not about the environment from a distance but from within its wound: the red earth, the black smoke, the claustrophobic winter smog and the brick-kiln landscape where human life and ecological life are crushed by the same hand.

This is an urgent novel, environmental in the deepest political sense, where ecology is not metaphor but material violence, etched into bone, breath, and memory. From the first page, the bhatti is introduced not merely as a workplace but as a malignant force: a “giant chimney” that “billowed thick, black smoke,” its evil eye fixed on the people below, its fumes settling like a curse on everything that grows, moves, or remembers. The soil is “red and loamy,” but its fertility is ironically what enables exploitation; the ground is “rent of all its green,” and the land’s depletion mirrors the emotional erosion of the families trapped there. Nothing in this novel is separate; environmental ruin is the grammar of survival.

The novel’s emotional power builds from its portrait of a family living under ecological and psychological siege. Lalloo returns to the bhatti each year like a pilgrim to a site of unresolved grief. His mother, broken by Jugnu’s death, rocks silently in the dark, hitting her head against a mud wall; an image so quiet yet so unbearable that it encapsulates the novel’s ability to wound without spectacle. His father, driven mad by guilt, crushes a sparrow during evening prayer, the small dead body lying on the “red earth” like a tiny omen of everything the bhatti destroys. Even Pinky, the child who has never known any world beyond this kiln, moves through life with dust in her hair and resignation in her bones.

Hassan does not dramatize ecological collapse; she shows how it seeps into routine: the families huddling under smog, the donkey’s ribs jutting out like exposed infrastructure, the rubbish heap’s stench rising “like a slap,” the winter sun hidden behind a “grey dupatta.” Pakistan’s environmental crises are often written about from the perspective of policy or urban anxiety. Hassan relocates those crises to where they originate, in the labour that powers our construction, our cities, our progress. This shift alone makes her voice distinct among contemporary women writers.

Yet the brilliance of When the Fireflies Dance lies not in its sociological clarity, but in its narrative urgency. The plot carries a quiet desperation: a daughter’s impending marriage, the father’s threat of taking another loan from the kiln owner Heera, the suffocating inevitability of debt bondage. With each decision the family makes, the reader senses the tightening of an invisible noose; one woven from poverty, exploitation, and an environment that offers no refuge.

In one of the novel’s most devastating passages, the family walks to Jugnu’s grave under a full moon. A few fireflies rise briefly above the mound—brief flashes of yellow-green light, appearing and disappearing so quickly that Lalloo wonders if they were even real. Those fireflies become the book’s emotional thesis: tiny survivals against total darkness, transient yet unforgettable. They are not symbols of hope, Hassan refuses such sentimentality, but signs of life persisting at the very edge of erasure.

Hassan’s prose is deeply controlled, almost understated, but beneath its restraint lies a ferocity. She writes in clean, sensory lines: the “smouldering behemoth” of the kiln, the “grey dupatta” sky, the taste of sewage on young Lalloo’s tongue, the brittle silence of a mother who cannot speak her grief. Her language is not ornamental; it is atmospheric. There is a journalistic sharpness in her observation, paired with a lyrical intimacy in her emotional intuitions. She writes like someone who has watched this landscape for a long time and refuses to look away.

In the broader tradition of Pakistani women’s writing, Hassan’s novel marks a shift; not away from the concerns of writers like Uzma Aslam Khan, Kamila Shamsie, or Bina Shah, but into a more grounded, class-bound environmental politics. Khan’s mountain ecologies, Shamsie’s cosmopolitan climate anxieties, and Shah’s gendered dystopias form important precursors, but Hassan’s vantage is different. Her eco-fiction grows not from the sublime or the futuristic, but from the inhaled toxins of Lahore’s outskirts. It is the environment as experienced by those whose names never appear in policy reports or climate panels. The women in her novel, Ami, Shabnam, Pinky, carry ecological disaster inside their lungs, their routines, their thinning futures. In this sense, When the Fireflies Dance expands the moral and imaginative territory of Pakistani Anglophone writing in a direction both urgent and overdue.

By the novel’s end, the reader realises that Hassan has accomplished something rare: she has written an environmental novel that is not about climate change statistics or heroic activism but about the intimate, inherited violence of a poisoned landscape. Her achievement is to show that environmental fiction in Pakistan must begin in the places where the air is unbreathable, the labour unpaid, the grief unspoken, where a firefly’s brief glow contains more truth about survival than any grand gesture.

A debut of startling maturity and visionary force, When the Fireflies Dance establishes Aisha Hassan as one of the most urgent new voices in Pakistan’s environmental fiction, one who understands that the land remembers everything we do to it, and sooner or later, our stories will have to answer back.

The review is written by Mudassar Javed Baryar, a doctoral researcher in English Literature at The University of Faisalabad (TUF), with a research focus on South Asian fiction, environmental narratives, and contemporary Pakistani Anglophone writing.