By: T.M. Awan

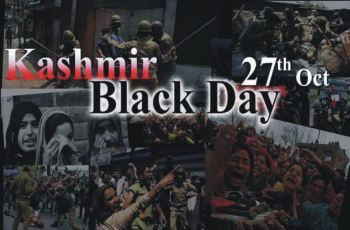

Seventy-six years ago, on October 27, 1947, the first Indian troops landed in Srinagar. The move, carried out under the cover of a hastily arranged “Instrument of Accession,” set the stage for one of the most enduring tragedies of the modern world, the denial of the Kashmiri people’s right to self-determination.

That right was not a vague moral aspiration. It was an international commitment, codified in United Nations Security Council Resolutions 47 and 80, endorsed by both India and Pakistan, and publicly reaffirmed by India’s own leadership at the time. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, speaking before the Indian parliament in 1952, declared unambiguously: “We have not annexed Kashmir. It is the people of Kashmir who must decide their own future.”More than seven decades later, that promise lies in ruins.

The story of Kashmir is often narrated as a territorial dispute between two nuclear-armed neighbors. But at its core, it is a question of justice and democratic principle. When British India was partitioned in 1947, princely states were expected to accede based on the will of their people and geographic realities. On July 19, 1947, the All–Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference, representing the majority Muslim population, passed a resolution favoring accession to Pakistan.

Yet in October that year, Indian troops entered the state before any legal accession had occurred. The so-called Instrument of Accession attributed to Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu ruler over a Muslim-majority population,was signed after Indian forces were already on Kashmiri soil. British historian Alastair Lamb, in “Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy”, documented that Indian officials had moved troops before any valid legal process. The accession, she concluded, was “manufactured under duress.”

The United Nations took notice immediately, recognizing Kashmir as a disputed territory and calling for a plebiscite to determine its future. That plebiscite never took place.

Instead of honoring its international obligations, India turned the valley into one of the world’s most militarized zones. Over 700,000 Indian troops now occupy the region,a ratio of one soldier for every ten civilians. Decades of curfews, arbitrary arrests, internet blackouts, and collective punishments have normalized a state of exception.

In August 2019, India unilaterally revoked Articles 370 and 35A of its constitution, the last remaining legal provisions that acknowledged Kashmir’s special status and internal autonomy. That move effectively annexed Jammu and Kashmir, stripping it of self-governance and opening the door for demographic re-engineering.

Since then, new domicile laws have been enacted to settle non-Kashmiris in the territory, altering the population balance in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention. International observers, from the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to Amnesty International, have described the situation as “systematic demographic manipulation.”

In 2025, India’s parliament passed the 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill, granting the Lieutenant Governor — an unelected federal appointee — sweeping powers to dismiss any elected minister or chief minister on the basis of pending legal cases or brief detentions. In a territory where dissent itself is criminalized, this provision effectively nullifies political autonomy.

The result is a democracy stripped of meaning. Elections are held, but not for choice — only for optics. Political participation under occupation is not empowerment; it is stage management.

Beneath the geopolitics lies a deep human tragedy. The Jammu Massacre of 1947, in which an estimated 280,000 Muslims were killed by Dogra and RSS militias, remains one of the least discussed genocides of the 20th century. In the decades since, thousands have disappeared; mass graves have been unearthed across the Valley.

The Kashmir Institute of International Relations (KIIR) and the Youth Forum for Kashmir (YFK) have chronicled these abuses, torture, sexual violence, and collective punishment under draconian laws like the Public Safety Act (PSA) and Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA). These reports echo the findings of the UN Special Rapporteurs and the European Parliament, which have repeatedly called for independent investigations, calls India continues to ignore.

The repression is not incidental; it is structural. Every aspect of Kashmiri life, from education to journalism, is policed. Universities are monitored, journalists detained, and even mourning gatherings are surveilled. The result is not stability but the institutionalization of fear.

Despite decades of documentation and diplomatic pledges, the international community’s response has been tepid at best. The UN resolutions remain valid, yet they are treated as relics of history rather than binding legal instruments. Western powers, quick to invoke human rights elsewhere, often silence themselves when Kashmir is mentioned,fearful of jeopardizing arms sales and trade with India’s billion-strong market.

This silence has consequences. By failing to enforce its own resolutions, the UN undermines not only its credibility but the very idea of a rules-based order. The Kashmir dispute is no longer a frozen conflict; it is a nuclear flashpoint that has triggered multiple crises between India and Pakistan. Each skirmish along the Line of Control risks spiraling into a catastrophe with global repercussions.

Pakistan’s position on Kashmir is grounded in international law, not territorial ambition. It views the dispute as the unfinished agenda of Partition — a moral and legal issue stemming from India’s defiance of UN resolutions. Islamabad continues to call for a peaceful resolution through dialogue and UN-supervised mechanisms.

While Pakistan’s diplomatic bandwidth is often limited by regional crises, its stance remains consistent: a plebiscite must decide Kashmir’s future. This is not a demand for secession but for self-determination,the same principle that underpins the UN Charter.

Kashmir today stands as both a wound and a warning, a test of whether international law still carries weight in an era of strategic convenience. The moral arc of history may bend toward justice, but only if nations act upon their obligations.

The United Nations has mechanisms, precedents, and moral authority. What it lacks is the will to enforce them. As global attention shifts from Gaza to Ukraine, from Taiwan to Tehran, the voices of eight million Kashmiris remain drowned in silence.

Yet silence does not erase struggle. Each year, as Kashmiris mark October 27 as Black Day, they reaffirm that the right to self-determination is not forgotten — only deferred. Their resistance, now spanning generations, is a reminder that no occupation lasts forever, and no promise can be buried indefinitely.

T.M. Awan

Senior Media and Strategic Communication Professional | International Relations Scholar

[email protected] | LinkedIn: @tahirmawan