The Taliban have won the war, but can they lead the peace?

EXCLUSIVE

Ishtiaq Ahmad

(Ishtiaq Ahmad is the former Vice Chancellor of Sargodha University and Pakistan Chair at Oxford University. In his previous career as a journalist, he reported the rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan in the mid-1990s. This is his exclusive write-up for The Islamabad Post.)

Now that the 20-year American imperial project in Afghanistan has become a footnote of history, it is time to focus on the victors of this war: The Taliban. Two comparisons are worth making here, one, the fundamental difference between the Taliban’s debut rise to power and their current conquest; and, two, their expected conduct in power this time around like or unlike the previous one. History, current and past, provides the answer.

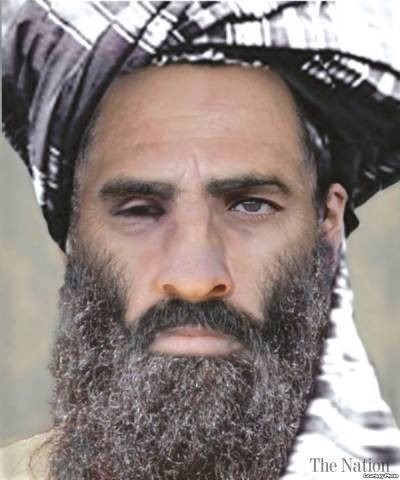

‘Who are the Taliban?’ So was titled my first news story from Kandahar in mid-1990s for an English daily in Pakistan. I was then a journalist and on a reporting assignment to travel to southern Afghanistan and investigate the instant rise of this Afghan militia. The Taliban had emerged as a ragtag group of madrassa militants under the leadership of Mullah Omar in response to years of Mujahideen infighting and oppressive rule. A major factor that contributed to the Taliban’s rise was the support from the war weary Afghan public for their swift enforcement of justice, disarmament and rule of law in the areas under their control.

The Inside Story

However, as the following snippets from the inside story of the Taliban headquarter in Kandahar city during the month Ramadan in 1995 shall reveal, the actual tale about this religious militia was even then quite different from its public portrayal:

“It’s Friday afternoon (Feb.17). As we enter the exit gate of the headquarter, I see a dozen or so people standing along the driveway, as if waiting for some important guests to arrive. Ali, my Taliban companion from Quetta, alerts me that the Emir-ul-Azeem (as Mullah Omar was titled then) is among them.I ask Ali to request his leader for a short interview, introducing me as a journalist from Pakistan.The message is passed. Mullah Omar looks at me and murmurs in Pashto asking whether I am fasting or not. Ali translates this to me. As soon as I say‘yes,’ the Taliban leader utters something in Pashto, and the entire group bursts into laughter. Ali is quick to tell mewhy: ‘Emir-ul-Azeem says these Pakistanis always lie.’ A chill runs down my spine, as the Qazi court is in session next door, awarding instant Islamic punishments.

“The conversation stops there, and I prefer to step aside. Soon the convoy of guests arrives. Mullah Abdul Salam Rocketi and his brother –recently released from the Quetta prison in a prisoners exchange deal with Pakistani authorities – aregreeted with warmth and love.After brief conversation with him, Mullah Omar writes down war instructions on a paper foil taken out of a Silk Cut cigarette packet, which Mullah Rocketi then passes on to his commanders ready for the battlefront in Ghazni, the ninth Afghan province under Taliban attack.

“It rains heavily that evening. So, I take refuge in a Taliban barrack, but it is crowded and scary. Lucky enough, I find refuge inside the headquarter. Following Traveeh prayers,in a side room, I sit with some Taliban Shoora members on the carpet. The discussion over Afghan tea is mostly about whether to attack Kabul now or capture more Afghan provinces.All of them hate Hekmatyar, the Hizb-e-Islami leader, and are impatient to destroy his Charasyab stronghold to reach Kabul. They want to establish the true Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan and also replicate it in neighbouring Muslim countries. A Shoora member from the North proudly claims that over 100 Taliban have already joined the Islamic fight against Russian occupation in Chechnya.

“Maulvi Amir Muttaqi (who would later serve as Information Ministerin the Taliban government is currently a senior Taliban leader) and Mullah Mansoor (who succeeded Mullah Omar as Emir-ul-Momineen and was later killed in a US drone strike in Baluchistan)) also join in later. The discussion moves to more substantive issues. Both of them say, their leader is very clear about enforcing Hanafi form of Sunni Islam in Afghanistan, which is also an ideal system of government for other Muslim nations. From Taliban conversations, I can easily guess that they carry a deep sense of pride, for defeating the communist Soviet Union; mixed with a deep sense of betrayal by the Americans, for using and then abandoning the Mujahideen. Hence, now they want to defeat the remaining superpower. When asked why they partnered with America before, they rationalise it by saying: ‘We joined the lesser evil to defeat the bigger evil, now we shall defeat the lessor evil.”

Hence, it is apparent from the anecdotal evidence presented above that the Taliban were quite clear at the initial stage of their debut rise to power about their political objective of establishing the Islamic Emirate in Afghanistan. They also shared the Al Qaeda’s agenda of exporting violence across the Afghan frontiers at the world stage, which is why the international terrorist outfit eventually found a safe haven under the Taliban rule. Moreover, the Taliban were also clear about their military strategy. Realising that mere public support was not enough to conquer the rest of Afghanistan, the Taliban were willing to forge unholy alliances with notorious Afghan warlords like Mullah Rocketi.

Yet, it took seven months for the Taliban to capture the south-western province of Herat in September 1995 due to the fierce resistance from its largely Shia Hazara population. And, it would take another year for the Taliban to conquer Kabul in September 1996. The last stronghold in the outskirts of the Afghan capital to fall was Charasayab, where the HizbeIslami forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar fought hard against the Taliban.The Taliban had first entered Mazar-e-Sharif in May 1997, but were routed within couple of days. They were finally able to capture this capital cityof the ethnically Uzbek-dominated northern province of Balkh in August 1998. Moreover, even while ruling Kabul, the Taliban were never able to conquer almost 10 percent of northern Afghanistan, where the Northern Alliance retained control, with its ethnically Tajik-dominated leadership intact in the north-eastern Panjshir Valley.

The Swift Victory

The stark difference between the rise of the Taliban then and now is the sheer speed with which they have conquered entire Afghanistan within a fortnight – surprisinglystarting the major military push from the north this time before the final assault on Kabul.

The Taliban also pursued an effective military strategy, which was to choke the Afghan regime by denying it trade revenues, and energy and communication means, then encircle Kabul from the north and the rest of the sides. Well before the Afghan capital swiftly fell to the Taliban on August 15, they had established control over almost all the provincial capitals, except the Panjshir Valley, including Jalalabad in the east. Mazar-e-Sharif also quickly fell, despite President Ashraf Ghani’s last-ditch effort to shore up alliance with the Uzbek militia of Rashid Dostum, who himself chose to flee.

Clearly, the hasty withdrawal of foreign forces – under the US-Taliban agreement that was signed last year without securing a ceasefire –emboldened the Taliban to reconquer the war-ravaged country without much resistance. With the US air support, the Afghan National Army was able to resist the Taliban for years, sacrificing tens of thousands of its soldiers. The denial of this support demoralised this army to the extent that its soldiers volunteered to surrender before the advancing Taliban combatants.

Despite this, the incapacitation of the Afghanistan National Defence and Security Force was a factor that contributed to the Taliban’s blitz. With widely known corruption, ineptness and factionalism, especially its rank-and-file dominated by the erstwhile Northern Alliance, there was no chance that it would act as the last resort for the beleaguered Ghani regime’s survival from the impending Taliban onslaught on the Afghan capital.

Once the Taliban reached the gates of Kabul, Ghani had no choice but to flee. First, he was betrayed by the old foxes like former President Hamid Karzai and the chief Afghan interlocutor for talks with the Taliban and his political rival, Abdullah Abdullah. Both are said to have played an instrumental role in persuading the provincial commanders not to resist the advancing Taliban en route to Kabul. Hence, it is no surprise that they are currently trying to reap the reward of this service by negotiating their role in the Taliban-led government.

Second, it is also believed that President Ghani had set up various meetings for August 15, and that he was forced to take the flight out of Afghanistan only after being told that a Taliban death squad had entered the city to execute him the same way as the Taliban had publicly hung the former Afghan president, Najibullah, by the pole in a Kabul square back in 1996. Thus, he simply feared or his life. Obviously, he had to subsequently create the pretence of “avoiding the bloodshed” for an act that was actually motivated by basic human instinct – and understandably so.

Like before, in the Taliban’s current conquest of Afghanistan, Panjshir Valley remains in the hands of their only opponents: Amrullah Saleh, the Afghan Vice President who has now declared himself as the President in Ghani’s absence and Ahmed Massoud, the son of legendry Afghan commander Ahmad Shah Massoud and the head of the National Resistance Front of Afghanistan. The Taliban may again find it hard to capture this remote and inaccessible place. However, the fact the Taliban are in control of the entire country and turncoats like Abdullah have betrayed the cause of the Shura-e Nazar founded and led by late Massoud in the valley, means the odds are in the Taliban’s favour.

To be continued

The author can be reached at [email protected]Twitter: @ahmadishtiaq