The 2022-23 budget is expansionary in nature in a constrained fiscal and external environment that is only going to push up deficits, and financing requirements, unless there is some respite on the external front.

An expansionary fiscal policy and a contractionary monetary policy continue to be at odds with one another. The budget, nevertheless, recognises that the country needs to snap out of a boom-bust cycle, and increase reliance on export-oriented growth, through increase in competitiveness — a welcome departure from a typical focus on import substitution.

The government is targeting a growth rate of 5 percent over the next fiscal year without expanding the current account deficit — a tough ask given the prevalent global macroeconomic scenario, and elevated commodity prices, which will continue to strain our already constrained resources. An inflation rate of 11.7 percent is also being targeted, which is highly optimistic considering the fact that the recent increase in fuel prices is yet to be captured completely, while the second-round effects of inflation will continue to shape up in the months to come.

As commodity prices globally continue to remain elevated, it will be increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to achieve the target, unless there is a crash in commodity prices, which seems highly unlikely for now.

The export target is estimated to be $35 billion, which will reduce overall current account deficit to 2.2 percent of GDP – a highly ambitious target that also assumes contraction in imports, which has rarely happened at least in the last twenty years.

Though more clarity is still awaited, rationalisation in duty structure of more than 400 items and nullification of regulatory duty on many items will provide a nudge to local industries to enhance competitiveness.

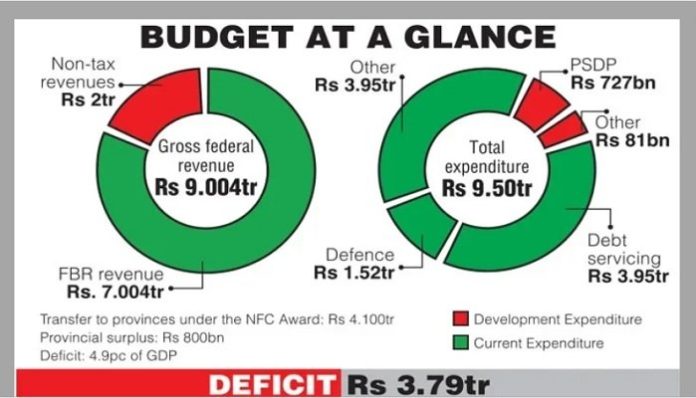

Public Sector Development Program (PSDP) allocation is at Rs800 billion, increasing from last year, clearly implying an expansionary fiscal stance despite a contractionary monetary policy. This suggests rollout of major infrastructure projects, including MainLine-1 (ML-1) of Pakistan Railways, which will improve connectivity throughout the country. The high impact laptop scheme, which had a substantial employment and revenue multiplier is also back, with an allocation of Rs17 billion to support IT infrastructure in the country, and basically laptop distribution.

The most vulnerable eight million households will get direct cash transfers of Rs2,000 per month in lieu of fuel subsidies, thereby avoiding market distortion, while also ensuring a soft lending can be managed for the most vulnerable.

Allocations to Benazir Income Support Program (BISP) have been increased to Rs364 billion from Rs250 billion last year to provide additional comfort to the most vulnerable segment of the population.

An additional Rs17 billion has also been allocated for price subsidy at Utility Stores and in the Ramzan package.

The budget speech also clearly identifies that allocation of capital towards non-productive sectors such as real estate reduces incentive to take risks in entrepreneurship, which results in lower capital formation, and increasing real estate prices making housing unaffordable for a vast majority of the country. It is imperative that such a lopsided structure is fixed.

The budget implies that the government policy will now enhance focus on vertical growth. The budget also introduces the concept of deemed rental income, wherein individuals having more than one property in their name valued at more than Rs25 million, would have to pay a tax at 1 percent of fair market value of that property. Similarly, a capital gain tax of 15 percent has also been imposed if any immovable property is sold within one year. This will ensure that speculative capital that has flooded the real estate market dries out, while prices may rationalise.

Another major departure from a regressive tax regime is a gradual move from withholding taxes to minimum taxes, and eventually adjustable taxes. The proof lies in the pudding, that is how the government executes the scheme.

What the government giveth, the government taketh back – this is largely the reasoning behind the increase in tax rate for banks, which has been increased from 39 percent to 42 percent, considering substantial profits that they are supposed to generate by lending primarily to the government.

In a surprise, yet welcome move, the tax bracket for salaried class has also been pushed up, enhancing the after-tax disposable income for a large chunk of the salaried class. Another innovative measure is bringing retailers into the tax net through electricity bills, with a fixed tax payment varying from Rs3,000 per to Rs10,000. Clarity is not available at this stage, but this will ensure that suddenly all retailers (with an electricity connection) can become taxpayers. Although similar schemes have been brought earlier as well, yet how this tax is imposed, and how it is transitioned towards a more economic activity-driven tax will remain a question of execution.

The budget despite being expansionary in nature is setting the right framework for reallocation of capital from non-productive areas to productive areas, which would have a multiplier effect on revenue and employment generation.

Bringing retailers into the tax net, while providing a breather to the salaried, and an expanded BISP umbrella are tweaks, providing some relief in a double-digit inflationary environment. This looks like an election budget, before an election budget was due. The challenges continue to remain, and the ability of the government to finance deficits in a double-digit inflationary environment will remain a formidable task.